William Zinsser: On Writing Well (Book Summary & Review)

“On Writing Well” by William Zinsser is an excellent book. So good, in fact, that I have decided it deserves a full review and summary with all the best advice it has to offer.

Even if writing isn’t your main trade, you can still benefit from getting better at it. There is need for well-crafted copy everywhere, be it for web pages, blog posts, social updates, project proposals, or even just emails. In addition, if you plan on earning money with an online business or as a freelancer, you should probably know how to write.

That also applies in times of generative AI—more so actually. Without knowing what good writing is, you won’t recognize bad writing, even when you are about to plaster it all over your website. AI is just a tool to work faster, you still need actual writing skills to turn what it produces into something useful.

Zinsser apparently saw this coming. To quote the book: “I don’t know what […] will make writing twice as easy in the next 30 years. But I do know [it] won’t make writing twice as good.”

With that in mind, what follows are my main takeaways from “On Writing Well.” I hope you find them as useful and inspiring as I did.

Introduction

“A writer’s job is to [say] something that other people will want to read.”

Zinsser’s book is not primarily about the rules of writing, such as where to put commas, hyphens, and em dashes. While it covers some of these aspects, the book’s main focus is on what Zinsser calls the “intangibles that produce good writing.” Namely, that’s confidence, enjoyment, intention, and integrity.

“Very few sentences come out right the first time, or even the third time. Remember this in moments of despair. If you find that writing is hard, it’s because it is hard.”

Something the book repeatedly stresses is the importance of editing and editing again. With each pass, try to make your writing tighter, stronger, and more precise. Eliminate “every element that’s not doing useful work” to bring more clarity and strength to your work. A helpful approach to do this is to read your text out loud and hear how it sounds.

Part I: Principles

“On Writing Well” is divided into several parts and chapters and this review and summary will mostly just follow the given structure.

The Transaction

“Ultimately the product that any writer has to sell is not the subject being written about, but who he or she is.”

Writing is a “personal transaction”; it means putting your personality down on paper. That’s the reason why all writers are tense (Can confirm – Nick). The two most important qualities you can convey with your writing are humanity and warmth.

Writers are craftsmen (and women), not artists. As a writer, your job is not to wait for inspiration to strike but to sit down and get to work. Don’t worry too much your writing process. “[…] There isn’t any “right” way to [write]. There are all kinds of writers and all kinds of methods, and any method that helps you to say what you want to say is the right method for you.”

Simplicity

“The secret of good writing is to strip every sentence to its cleanest components.”

Clutter is what makes writing bad. Its role is usually to try to sound important. To get rid of clutter:

- Eliminate all words that don’t serve a purpose.

- Replace long and complicated words with short and simple ones.

- Get rid of adverbs that mean the same as their verb.

- Use active instead of passive voice. Or, at least make sure your passive constructions make it clear who performs the action in the sentence.

Why the need for simplicity?

Because your readers are bombarded by distractions every day. You are competing with everything else vying for their attention. Your job is to catch your readers’ interest and keep them interested so that they will continue from one sentence and paragraph to the next.

(Mind you, the latest edition of “On Writing Well” is from 2006, right before distraction became a global pastime.)

Clear writing is the result of clear thinking and thinking clearly is a conscious act. Therefore, “a clear sentence is no accident.” Constantly ask yourself what exactly you are trying to say. Did you say it? Is it understandable even to someone encountering the subject for the first time?

Clutter

Most drafts can be cut by 50 percent without losing information or the author’s voice. Here are some concrete examples of clutter and how to deal with them.

Prepositions attached to verbs that don’t serve any purpose:

- “to head up a committee” → “to head a committee”

- “to face up to problems” → “to face problems”

Words that say the same thing or say it in a more complicated way:

- “personal feeling” → “feeling”

- “to experience pain” → “to hurt”

Complicated euphemisms (especially prevalent in the worlds of business and politics):

- “depressed socioeconomic area” → “slum”

- “waste-disposal personnel” → “garbage collectors”

Long words that are no better than short words:

- “assistance” → “help”

- “numerous” → “many”

- “remainder” → “rest”

- “to implement” → “to do”

- “to attempt” → “to try”

The same applies to phrases:

- “due to the fact that” → “because”

- “he lacked the ability to” → “he couldn’t”

- “until such time as” → “until”

Finally, there are redundant descriptions like:

- “tall skyscraper” (what skyscraper isn’t tall?)

- “to smile happily” (that’s the default of smiling, no?)

You can find plenty more examples in the book.

Style

Style is as individual as the writer. You can’t steal it or take on someone else’s. You can try out different styles but you have to ultimately find your own.

Style matters because readers will know when you’re pretending to be someone else. Therefore, a fundamental writing rule is: be yourself. That means, be willing to take a stand, have an opinion, and believe in it.

This advice is very hard to follow, it needs relaxation and confidence, both not easily found in writers (Come on, man, really!?).

Zinsser does not offer a solution for this. The only consolation he has is that you are not alone. Sometimes it will be better, sometimes it will be worse.

One thing you can do is try not to overwhelm yourself. Just begin. Things will start flowing at some point, and you’ll start to sound like you.

The Audience

Write for yourself. Don’t try to guess what an anonymous reader or your editor wants to hear. They won’t know until they read it.

In addition, write to please yourself. Give yourself permission to have fun while doing it. Don’t worry if someone else will get your humor. If you enjoy yourself during the process, your readers will feel it, at least the ones worth writing for.

Remember, the ultimate goal is to express your personality. You still need to invest in your craft to do it in a form worth reading, but that’s just the means to the end. So, “relax and say what you want to say.”

Words

“[…] develop a respect for words and a curiosity about their shades of meaning that is almost obsessive.”

“Remember that words are the only tools you’ve got. Learn to use them with originality and care.”

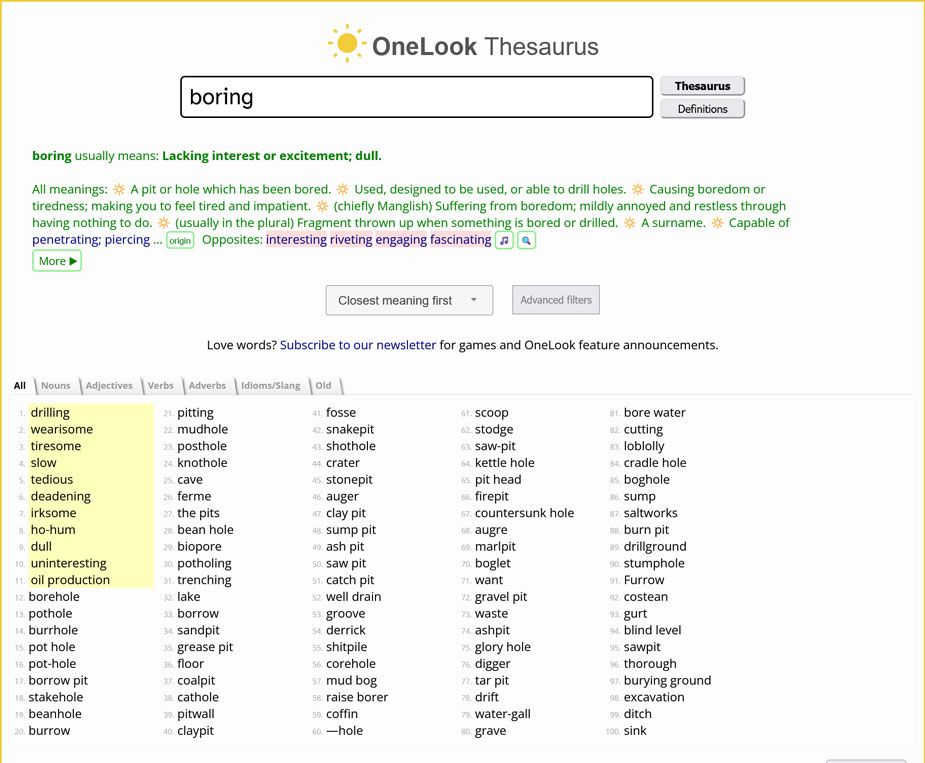

Avoid tried-and-true (i.e. boring) words and phrases. Don’t reach for the nearest cliché. If you don’t surprise readers, you will bore them to death.

The only way to keep from doing that is to care deeply about words. Understand the small differences between terms that seem to mean the same thing. Get yourself a thesaurus (I can recommend OneLook).

Pay attention to how your writing sounds. Readers sound it out in their head. That’s why rhythm and devices like alliterations are important.

Finally, if you want to learn to write well, read the people who are producing the kind writing you aspire to and then figure out how they do it.

Usage

Keep up with how words are used. New ones come into fashion and old ones are discontinued every day. However, separate word usage from jargon, meaning pompous words that aim to sound important.

Some jargon is necessary in certain disciplines, e.g. computer science. But don’t adopt words into everyday language just because they exist and sound fancy. If a word for your purpose is already available and allows you to express yourself clearly, it’s absolutely fine to use it.

Part II: Methods

“The only way to learn to write is to force yourself to produce […] words on a regular basis.”

Writing is ultimately problem solving. Whether it’s problems of obtaining facts, organizing your material, or one of approach, attitude, tone, or style, you have to confront and solve them.

Unity

“Unity is the anchor of good writing.”

There are different kinds of unities you need to adhere to in your work:

- Pronouns — You can write in the first, third, or even second person. It’s up to you. But make a decision and stick with it.

- Tense — Avoid going back and forth between past and present tense, unless, of course, the narrative demands it.

- Mood and attitude — Your voice can be casual or formal , funny, personal, or absurd—as long as it’s consistent.

Unity maintains order and keeps readers interested and comfortable. A lack of unity is confusing and off-putting. It makes the writer disappear and takes the reader out of the experience.

Scope

“Decide what corner of your subject you’re going to bite off, and be content to cover it well and stop.”

Another consideration of unity is scope. This is a difficult decision especially for nonfiction writers, who often want to cover “everything” about a given subject.

That’s an impossible task, especially because things constantly change. For that reason, every writing project is always a reduction.

The solution is to think small, which will also help you stay motivated. If your writing project feels like a monster, you’ll lose your enthusiasm and readers are the first to notice.

A good way to introduce focus is to decide on “one provocative thought” you want to leave your readers with. Just one, not more. What single point are you trying to make?

This approach gives your writing focus. It makes decisions about tone and attitude and the best way to arrive at your destination.

Once you have your unities in place, it allows you to tackle any material. At the same time, you don’t have to be a slave to them. Often, you might find that, while you are writing, your material leads you in a different direction.

That’s normal, so don’t fight it. Trust your material, adjust as you go along, and make everything fit together during editing. As long as the unities are present in the final piece, you are good.

The Lead

“The most important sentence in any article is the first one.”

The purpose of your first sentence is to get readers to continue to the second. That one should get them to read the third, and so on.

There is no set formula for how long the lead should be. The only valid test is: does it work?

Your lead must capture your readers’ attention right away and hold on to it. They want to know what’s in it for them if they continue, and quickly. Some ways to accomplish that are:

- Freshness and novelty

- Paradoxical information

- Humor

- An unusual idea or interesting fact (often discovered during research)

- A question

- Telling a story

After the first hook, provide hard details about the purpose of the piece and why someone should read it. Focus more on details and less on entertainment. Every paragraph should build on and amplify its predecessor.

Here’s an example of one of my best introductions:

Pay special attention to the last sentence of each paragraph. Try to include some extra humor here or a surprise to drive readers forward.

Again, avoid clichés and tried-and-true lead-ins. My favorite example from one of Zinsser’s own articles: “I’ve often wondered what goes into a hot dog. Now I know and I wish I didn’t.”

Tip: If you get really funny quotes, find a way to use them. Always collect more material than you plan on using, you never know what fact is going to make or break a piece.

In addition, look for material everywhere. Be curious about life. Read signs, billboards, package instructions, graffiti, bank statements, electrical bills, restaurant menus—everything you can find. It’ll help you understand society better and give you ideas and possible leads that nobody else uses.

The Ending

Just as important as knowing how to begin a piece of writing is knowing how to stop—and when. You should give almost as much consideration to choosing your last sentence as you do to picking your first. An article that doesn’t stop where it should becomes a drag and leaves a bad taste in readers’ mouths.

For your ending, don’t simply summarize everything you’ve said before. It will break the tension and readers will feel your own boredom in the sentences. The perfect ending is one that takes readers slightly by surprise and yet seems exactly right. “On Writing Well” contains the absolutely hilarious example below from a piece William Zinsser wrote about Woody Allen in the 60s.

Your ending can seem a little too soon or abrupt or out of the blue. Again, the only litmus test is: does it work?

Stop when you are ready to stop. If you have laid out all the facts and made your point, get out as quickly as you can. It usually only takes a few sentences.

The ending should encapsulate the idea of the entire piece and also jolt readers with its quality or surprise. Try to bring the story full circle by echoing a sentiment you introduced in the beginning. It’s a satisfying conclusion to a journey.

Another thing that often works is to use a quote from your research, especially if it has a sense of finality, is funny, or unexpected like the above. If it surprises and delights you, chances are high it will do the same for your readers.

Bits & Pieces

This chapter contains a smattering of writing tips that didn’t fit into any other part of the book.

Verbs

Verbs are your most important tools. They push sentences forward and lend them momentum.

Use active verbs unless there is no other comfortable way of saying what you want. Active verbs allow readers to visualize an action by giving them a person who performs it. Active verbs are also colorful and often carry their meaning in their sound or imagery. In writing, the difference between active and passive verbs is like the difference between life and death.

In addition, short verbs are better than long verbs. Avoid verbs that need an appended preposition, go for “start” or “launch” instead of “set up”. Don’t say “stepped down”, rather say “resign”, “retired”, or “got fired.” Be precise in your use of verbs.

By the way, if you are struggling with using active verbs in your online content, use the Yoast SEO or All in One SEO readability modules to tell you when you are using too many passive sentences.

Adverbs

“Don’t use adverbs unless they do necessary work.”

Most adverbs are needless clutter. You often find them attached to verbs that already carry the same meaning, e.g. “to blare loudly” or “clench your teeth tightly.” “Blare” and “clench” already imply the meaning of the adverbs. The same goes for other instances like “effortlessly easy”, “slightly spartan”, or “totally flabbergasted.”

Adjectives

Adjectives are similar to adverbs—most writers use them with nouns which already contain the meaning of the adjective. Examples:

- “brownish dirt”

- “yellow daffodils”

Don’t use adjectives solely as a decoration. An adjective should be present because it makes sense and contributes something important.

Little Qualifiers

“Good writing is lean and confident.”

Qualifiers are words like “a bit”, “a little”, “sort of”, “kind of”, or “pretty much.” They dilute your writing and make it less persuasive.

If you are confused, tired, or depressed, be it. Don’t qualify it further. It takes away your readers’ trust in what you are saying. They want a writer who believes in themselves and speaks with authority.

Punctuation

Some thoughts on different punctuation markers of the English language:

- Period — Most writers don’t reach it soon enough. If you are struggling with a long sentence, it’s probably because you are trying to make it do more than it reasonably can. Try breaking it down into two or three shorter ones. Only few writers can pull off a style of long sentences.

- Exclamation point — Only use it to achieve a particular effect. Most of the time, it’s better to arrange your sentences so that they achieve the same outcome or emphasis without an exclamation point. Never use it to point out humor, being funny is best achieved by understatement.

- Semicolon — This punctuation mark is a bit old school and should, therefore, be used sparingly by modern nonfiction writers. It introduces a pause in a sentence and is great for joining related or opposite thoughts. But most often you should use a period or dash instead.

- Dash — The humble dash (“—”) is a very useful writing tool that you can use in two ways. One is to amplify or justify a thought in the preceding sentence—like so. The other is to use two dashes to set apart a separate thought—like this one—within the middle of a sentence. This can save you from using a second, separate sentence.

- Colon — Many functions of the colon have been taken over by the dash. Zinsser sees its main purpose as introducing a short pause, often before listing several items.

Mood Changers

These are tools that inform readers that a change in the feeling of the writing is coming. Examples:

- “but”

- “yet”

- “however”

- “instead”

- “thus”

- “meanwhile”

- “later”

Mood changers are clear signposts and make readers’ lives much easier.

If you’ve been taught not to start sentences with “but”, you should unlearn that rule as quickly as possible. There’s no stronger word to announce a contrast in your writing.

If you use “however” in order to avoid repetition, introduce it as early in your sentence as you can. But not at the start, where it “hangs […] like a wet dishrag.”

“Yet” is similar to “but” though its meaning is closer to “nevertheless.” Both “yet” and “nevertheless” spare you the effort of having to summarize the previous sentence.

Mood changers make your writing a lot tighter. They are indispensable for keeping your readers on track and aware of where they are.

Contractions

Definitely use contractions like “I’ll”, “won’t”, “can’t”, “we’re”, etc. They add warmth and personality. But only use them when your writing can accommodate it.

The only exception is “I’d”, “he’d”, “we’d”, etc. These can have multiple meanings (e.g. “I had”, “we would”) and can be confusing for that reason.

Don’t invent contractions like “could’ve” (or, my favorite, “y’all’d’ve”), stick with those that appear in a dictionary.

That and Which

“That” is used for further describing something. “Which” is for adding a qualification, like a description, location, or explanation. Always use “that” unless it makes your meaning ambiguous.

For example:

- “Eat the food that’s in the fridge.” → Eat the food in the fridge, not the one on the table.

- “Eat the food, which is in the fridge.” → There is only one type of food discussed here and it is in the fridge.

If your sentence requires a comma to be clear, it’s probably a case for “which.”

Concept Nouns

Concept nouns are nouns that describe a vague idea instead of a clear action:

- “The common reaction is incredulous laughter.”

- “Bemused cynicism isn’t the only response to the old system.”

- “The current campus hostility is a symptom of the change.”

These sentences are dead. They have no people in them and no working verbs, which makes it very hard for the reader to visualize anything that’s happening. The entire meaning is transported by impersonal nouns describing something indistinct.

Better solutions are:

- “Most people just laugh with disbelief.”

- “Some people respond to the old system by turning cynical […].”

- “It’s easy to notice the change—you can see how angry all the students are.”

Nounisms

A “nounism” means using two or three nouns where one noun or verb would be enough:

- “money problem areas” → “being poor”

- “precipitation activity” → “rain”

Again, use verbs instead and write in a way that allows readers to imagine what’s happening.

Overstatement

This means exaggerating to the point that it becomes ridiculous and implausible:

- “The living room looked as if an atomic bomb had gone off.”

- “I felt as if ten 747 jets were flying through my brain […].”

No reader is going to believe this and it’s off-turning. Humor should be more subtle than this.

Credibility

Continuing in the same vein, don’t squander your readers’ goodwill by inflating facts, situations, and events beyond what’s true. If readers catch just one such incident, they won’t fully trust anything else you write. It’s not worth the risk.

Writing Is Not a Contest

As a writer, you are running your own race. Avoid seeing yourself in competition with others, it will paralyze you. Instead, focus on studying and mastering your craft. Go at your own pace, you are only in competition with yourself.

(If you figure out how to do that, share it with the rest of us in the comments.)

The Subconscious Mind

Your subconscious is more involved with your writing than you think. It continues to work on writing problems even when you are not actively putting words down. Oftentimes, solutions will present themselves when you take some time off, come back to your work the next day, or are busy with another activity. Trust that they will be there when you need them.

The Quickest Fix

Often, the best way to deal with a difficult sentence is to delete it entirely. It’s also often the last solution writers will consider.

When you find yourself in a situation where you are struggling to make a sentence fit, ask yourself: “Do I need it at all?” There is a good chance the answer is no.

Paragraphs

Writing is visual, readers see the entirety of your text before they even start reading. Therefore, keep your paragraphs short. They are your readers’ roadmap and show how you have organized your ideas.

Shortening paragraphs creates air around them and makes your text inviting instead of scary and overwhelming. This is especially true for newspaper articles where paragraphs are most often set in narrow columns.

But don’t simply chop up thoughts that belong together to create space. Each paragraph should have its own integrity and structure.

Sexism

Make sure to be inclusive in your choice of pronouns and the words you use for describing different genders.

Avoid:

- Words that are only applied to one gender, e.g “lady lawyer”, “housewife.”

- Phrases that show possession of people by the family male or reserve certain roles for one gender, such as: “Doctors often neglect their wives and children.”

- Words that include a particular gender, like “chairman” or “washwoman.”

Instead:

- Rewrite sentences so that they include everyone: “Doctors often neglect their families.”

- Use gender-neutral words like “chair” or “company representative.”

- Go with a verb instead: “Speaking for the company, Ms. Jones said…”

- Summarize the male and female version under a generic word, for example, “performers” instead of “actors” and “actresses.”

For pronoun usage:

- Turn to the plural instead of using singular pronouns: “All employees should decide what they think is best for them […].” But don’t overdo it or it will “turn your writing to mush.”

- Use “or” as in “[…] what he or she thinks is best for him or her.” But, again, do so sparingly. Avoid using constructions like “he/she.”

- Talk to the reader directly: “You’ll often find”, “we often find” instead of “the writer often finds that he…”

Zinsser notes that he is not in favor of words like “chairperson” or “spokeswoman”, calling them “makeshift words, sometimes hurting the cause more than helping it.”

Rewriting

“Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it’s where the game is won or lost”

Your first draft is pretty much never the final product. This is a hard idea to accept for many writers. But don’t think of it as an unfair burden, consider it a gift instead. Writing is a process, not a product.

Rewriting does not mean writing a first draft, then a second, then a third. Instead, most of it is improving upon what you produced the first time around. If you want to see this in action, the book has a detailed example of a first draft with notes on how to improve it.

While rewriting, focus especially on the narrative flow. Make sure you don’t lose your readers on the way. Give them everything they need to easily follow along from start to finish. At the same time, ruthlessly cut unnecessary words, improve precision, connection, and the pleasure of reading.

Trust Your Material

Focus on what you have to report, less on how you report it. Your duty is to find interesting enough material so that it doesn’t need gimmicks to come across as interesting.

Avoid over-explaining. Readers need enough space to draw their own conclusions about what you tell them.

Go With Your Interests

“No subject is too specialized or too quirky if you make an honest connection with it when you write about it.”

Select topics you are genuinely interested in. You will write better and with more enjoyment and it will show up on the page. Don’t shy away from topics dear to your heart because you think others won’t care about them. Your passion will be palpable and help engage readers.

Part III: Forms

“Good writing is good writing, whatever form it takes and whatever we call it.”

This part of the book discusses ways to write specific forms of nonfiction and about certain topics, particularly:

- Interviews

- Travel articles

- Memoirs

- Science and technology

- Business writing

- Sports

- The arts

- Humor

Each chapter contains solid advice and lots of examples. If you are interested in writing about any of these areas, I recommend you read the respective chapter in full. I was more interested in the general writing tips contained in this section, so I have summarized them here:

- Interviewing is a skill you can only get better at by doing it more.

- Always look for the human element, the stories of people behind the facts. Readers identify with people, not abstractions.

- Be very selective in your material. Find unusual, distinctive, and unique details to write about.

- Assume the reader knows nothing.

- Before you can teach something to someone else, you first need to understand it yourself.

- Hang around the places you write about, listen to the people you meet there, and interview them in depth.

- You need to like or even love what you critique or review. If you don’t, don’t write about it.

- Express your opinion firmly, take a stand with conviction.

- If you want to write with humor, first master language.

Part IV: Attitudes

The final part of the book is about mindsets toward writing and life as a writer.

The Sound of Your Voice

“My commodity as a writer, whatever I’m writing about, is me.”

Develop and preserve your voice no matter what subject you are covering. You want readers to be able to recognize you.

Avoid breeziness and condescension. Be confident. Don’t try to ingratiate yourself with your readers. They don’t want to be patronized and will stop reading if they think you are talking down to them.

Develop taste. It’s an intangible quality you have to acquire over time. Knowing what not to do is half the battle. To improve your literary tastebuds, find the best writers in your field and read them out loud. Study their use of language, then find your own way.

Enjoyment, Fear, and Confidence

Writing is lonely work, so you should at least keep yourself entertained while doing it. Leave in sentences and words that amuse you. There will be others who also find them funny and those are the people you want to talk to.

To be a writer, you need to be self-motivated. You have to turn on the switch, nobody will do it for you.

Fear is part of the process, especially for nonfiction writers. One of the reasons is that, in contrast to fiction, more things can be objectively wrong in nonfiction.

But fear most often arises when you see writing as a chore. Stop worrying if the first draft is crap. You’ll get another crack at it tomorrow and the days after.

Develop confidence by writing about topics that interest you and that you care about. Use it as an excuse to give yourself an education in almost any area you want. Doing so also allows you to have an interesting life.

Bring some part of yourself to every story. Write about people you respect. Be sincere in your efforts to understand, it helps to open doors. Don’t be afraid to ask dumb question, after all, your job is to make topics accessible to the public.

The Tyranny of the Final Product

Fixation on the finished article distracts you from making important decisions about its shape, voice, and content and is not conducive to good writing. If you focus on the process instead, the final product will take care of itself.

Find the why behind what you want to write:

- Why is the topic important to you?

- What is the connection to yourself?

- How has it peaked your interest or touched your emotions?

One of the biggest problems is compression—finding an interesting and contained narrative in a huge mess of information. To combat that, look for examples on the small scale that tell the larger story, for example, a single family in a single town that tells the story of an entire area.

Again, focus on the process, not the product. Free yourself from the deadline, relax and enjoy yourself. Allow as much time as is needed for the journey.

A Writer’s Decision

“As a nonfiction writer you must get on the plane. If a subject interests you, go after it, even if it’s in the next county or the next state or the next country. It’s not going to come looking for you. Decide what you want to do. Then decide to do it. Then do it.”

Writing requires making decisions. You need to make choices about:

- Which topic to cover

- How to structure your article

- Maintaining sequence and logic

- Keeping tension from one paragraph to the next

- Preserving a narrative to pull readers along

- Specific word usage

This chapter goes over one of Zinsser’s own articles to demonstrate his approach to making these decisions. It’s a great dissection of his work, I highly recommend reading it.

The chapter reiterates many earlier points:

- Begin your article with one provocative idea. Build on it so readers stick around for the entire journey.

- Express one thought per sentence. Break them up if you have to.

- No writing decision is too small to be worth spending time on. Zinsser spent an entire hour on a single sentence in the example article in this chapter.

- Break your piece down into manageable chunks and tackle each one individually.

- Trust your material.

- The story will often tell you where to end it. When it does, look for the fastest way out.

Writing Family History and Memoir

“Memories too often die with their owner, and time too often surprises us by running out.”

This part of “On Writing Well” discusses “how to leave some kind of record of your life and of the family you were born into.” It stresses that writing a memoir is a great tool to come to terms with your life’s story and work through some of its toughest parts. It’s worth doing even if you don’t plan on publishing the result.

Like Part III, the focus here is on a specific form of writing, so if you plan to produce a memoir, I recommend you read the entire chapter. It has many good tips on how to approach such a task, what to do, and what not to do.

The single best tip I found in this chapter is advice on how to undertake monumental writing assignments such as covering your own life story. The answer is: In manageable chunks.

Don’t visualize the finished product. Simply sit down and record significant events in your life that you still remember well. Simply collect them, they don’t have to be related to each other. Trust what your subconscious serves up to you.

Do this for a few months. Then, one day, read through everything you have compiled. It will tell you what your memoir is about and what it’s not.

Write as Well as You Can

“Quality is its own reward.”

90 percent of success as a writer is mastering the tools mentioned in this book. The rest is natural gifts and—most importantly—the desire to improve and get better, to take “an obsessive pride in the smallest details of your craft.”

Think of yourself as part entertainer. It doesn’t matter how you do it—humor, anecdotes, quotes, you name it. Your style, your personality on paper is your main marketable asset. Fiercely protect it during the editing process, be serious about what you write and how you write it. Do that and deliver quality on time and you should never want for work.

“On Writing Well”—Personal Takeaways

I found Zinsser’s book inspiring every time I picked it up. It had a real impact on the way I work. In the final part of this review/summary, I want to go over the lessons from “On Writing Well” that most stuck with me.

Be Yourself and Enjoy the Work

If you are a freelance content writer, it’s easy for writing to become a chore. It’s a job after all, with deadlines to meet and client expectations to fulfill. Enjoyment isn’t usually a priority.

“On Writing Well” reminded me that it doesn’t have to be that way. It helped me remember that I like working with language and that it can be fun if you let it.

In addition, it hammered home the idea that expressing your personality is a good thing. I first picked up this idea from the fantastic Laura Belgray over at Talking Shrimp (check her out, she’s great) and it’s something I’ve been trying to do more in recent years. I mean, just look at my about page. The second paragraph contains the words “donkey balls” and it doesn’t get better from there.

But I don’t only do this for myself, I’m also trying to have more fun and be more myself in my client work. While it doesn’t reach the level of “donkey balls”, I did recently write one of the best introductions I have ever penned. Because I partly wrote it to entertain myself and you can tell that I enjoyed myself.

In addition, the other day I was writing a tutorial about how to create a church donation form. On the surface, that’s a pretty dry topic if you ask me. But I made it more entertaining for myself (and, hopefully, the readers) by trying to reference as many biblical phrases as possible (unfortunately, my editor only left one in).

Being a silly goose, putting in stupid little jokes like that makes me smile and I hope it can do the same for the audience. It also makes writing a lot more enjoyable. While I still focus heavily on providing value, getting the facts straight, and delivering them in an easy-to-understand way, I also increasingly try to be myself while doing it. So far, nobody has complained (at least, not to my face).

Writing Is Learning

One of the things I deeply related to in “On Writing Well” was the part about using writing to learn.

I have been doing this for years, often unwittingly. I frequently choose topics for blog articles because I want to know more about them. Other times I want to share information I learned for myself and that I want others to benefit from. Finally, I also learn a lot by writing about topics I know nothing about, often because clients request them of me.

This is also pretty much the basis for my entire career. Most of what I do is solve problems and share the solutions. It’s why I often say that I get paid to do things I’d happily do for free.

Learning is also a major part of why this blog exists—to be a lab for experiments and exploration. I really enjoy getting to pick my own topics, choosing something I am passionate about, and investigate it in my own tempo. It’s a refreshing change of pace to take your time, especially now, where everything seems to be urgent and everyone seems to be under pressure to constantly produce.

I Might Have a Focus Problem

A part that I found very interesting was when Zinsser talks about unities. I noticed I usually don’t make conscious decisions them, instead, I sort of settle on them while writing.

Something that really hit home though were the parts about reduction and compression. I definitely have want-to-say-everything-there-is-to-say-about-a-topic syndrome (it’s a real thing, look it up).

I mean, I only wrote close to 16,000 words about WordPress SEO plugins. In addition, this review and summary of “On Writing Well” also started close to 9,000 words (though the final product is more around 7,000).

You see what I mean?

It’s something I’ve become a lot more conscious of reading Zinsser’s book. It also has made me more ruthless in my editing process. I now delete more sentences and paragraphs I would’ve kept in the past. Though I still like to be thorough, I think it makes my writing tighter and more streamlined.

Finally, I’ve also become more conscious about the way I end blog posts. I don’t think all of the advice for endings in “On Writing Well” is applicable to content like WordPress tutorials. Sometimes, it really helps to summarize the main steps of an entire post in the conclusion. But I now try to go beyond that and find a new and interesting or valuable point to leave readers with.

The Book Itself Is a Lesson in Great Writing

Something that’s important to point out is that just paying attention to Zinsser’s own use of language will teach you a lot about good writing. The book contains so many sentences that are inspiring in themselves in their wit, clarity, and humor. I mean, there is a reason I included as many direct quotes from the book as I did.

The quality of the writing also posed an interesting problem when you want to write a summary and review of “On Writing Well.” The book itself is so polished and well-composed that it’s very difficult to sum up its content any clearer than what’s already on the page. That’s probably the level of writing we should all aspire to, I know I do.

Rules for Good Writing Are Surprisingly Timeless

The latest edition of “On Writing Well” is from 2006. Naturally, that means some of its advice has become dated. For example, at one point, Zinsser marvels at the new possibilities offered to writers by computers and word processors.

He also talks about bringing a tape recorder to interviews, something that, in times of smartphones and dictation software, is a bit of an anachronism. I also found his advice on inclusive writing dusty at times and more complicated than it needs to be.

But the impressive thing is that this is the only out-of-date advice that stood out to me. Even though the book is almost 20 years old (in fact, older, the first edition came out in 1976), its insights are still rock solid. It appears the rules for good writing don’t change very much.

“Quality is Its Own Reward”

The above is one of my favorite quotes from “On Writing Well.” I think it’s because, at the end of the day, I just want to produce work I am proud of and that’s meaningful to me. Very little beats the feeling of creating something from nothing and putting your heart and soul into it until it comes out right.

I don’t think I’m alone in this. The freedom to create and make a living with meaningful work is probably what drives many freelancers and entrepreneurs. We accept the hardships and insecurity that can come with being self-employed because we’d rather have that than work a job that slowly kills our souls.

I know I do. It’s why my homepage says “make money online, doing work you love.” It’s why, even in times of generative AI, most of what I put out is pretty much hand-made. Because I like doing this, because it’s what I want to do, and because I find it incredibly gratifying.

“On Writing Well”—A Book Almost Everyone Should Read

To repeat my sentiment from the beginning: “On Writing Well” is excellent. It contains the perfect mix of practical writing advice you can apply directly to your craft while also discussing more immaterial parts of working with words, like mindset and general principles. I definitely learned a lot.

In addition, as mentioned, the writing itself is just so very good. Almost every sentence of “On Writing Well” delivers value. While reading it the first time, I kept sending lines to a writer friend of mine. I also deleted dozens of additional quotes during editing I had originally included.

In short, I fully endorse that anyone who has even a fleeting interest in or need for writing read this book. Even though it may seem that most of what “On Writing Well” has to offer is already included in this summary, there is a lot more to learn, especially from the many examples Zinsser uses and discusses.

Finally, thanks so much for reading. I’d love it if you would leave a comment below and take part in the discussion.

What advice from “On Writing Well” stood out for you? How are you planning to use it in your work? Any other thoughts or feedback? I’d love to hear from you!

Leave a Reply